Japan has been renowned for its “anime” (animated films) for decades. Since the 1980s, the undisputed king of this field has been Hayao Miyazaki and his production company, Studio Ghibli. To say Ghibli is famous is an understatement. The influence of the studio, and of Miyazaki, on the country, and indeed the world, is profound, and reaches far beyond animation. Miyazaki’s accomplishments, and his enormous success, have made him one of the most respected animators in the world.

The word “ghibli,” incidentally, is an Italian word meaning sirocco, the hot wind that blows through the Sahara. It also refers to a type of Italian reconnaissance airplane during World War II. As his classic films “Kaze no Tani no Nausicaa” (“Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind”), “Kurenai no Buta” (“Porco Rosso,” or “The Crimson Pig”) and “Majo no Takkyubin” (“Kiki’s Delivery Service”) clearly demonstrate, Miyazaki loves airplanes, and Italy.

For any fan of animation, the thoroughly delightful Ghibli Art Museum, in the leafy Tokyo suburb of Mitaka adjacent to Inokashira Park, is a touchstone, but is well worth a trip for anyone, especially if they have kids in tow. Access is easy on public transportation, but be warned — you can’t just show up and buy a ticket. You have to get them from a Lawson convenience store, or a Japan Travel Bureau, after showing your passport. The museum is quite small, and so popular that it would get hopelessly crowded if visitor numbers were not strictly limited. Some tickets are available outside Japan through JTB and other Japanese travel agents.

Anyone who has seen a Studio Ghibli film will see Miyazaki’s influence in the design of the museum building, with its cascade of vegetation, glowering windowshades and other strange structural details. A full-size (that is, very large) Totoro, the friendly woodland ghost from “Tonari no Totoro” (“My Neighbor Totoro”, stares blankly from a ticket booth at the entrance; the real entrance is further along the path. The interior is full of hand-crafted stained glass lamps and glass balls in the balustrades that catch sunbeams and send shafts of light through the rooms. The reception area contains rooms with child-scale entrances, and beautiful sunny frescoes on the ceilings. The main hall contains a maze of spiral staircases, terraces, bridges and passageways.

The museum is packed with all kinds of magical details and references to Ghibli films. The first floor is devoted to the tools of the animator’s trade, and the history and technology of animation, with demonstrations using characters from Ghibli’s famous films. One exhibit uses a series of models of characters from “Tonari no Totoro” that spin around on a turntable at high speed. Strobe lights hit the spinning models, and suddenly the transforms into a scene of Cat Buses running around a tree. The remarkable thing is that, even after you see how it’s done, and even start and stop the turntable a few times, it still seems like magic. Likewise, with another exhibit, a real movie projector runs a movie, and visitors can peer through viewers set up around it to watch the single frames magically coalesce into a moving picture.

A movie theater on the first floor shows exclusive short animated films. We saw “Koro’s Big Day Out,” a short about a lost puppy that delighted the audience, which was mostly children. The ticket is three frames from an animated film (mine was from “Majo no Takkyubin,” I think).

Also on this floor is an exhibit of an animator’s studio from the days of hand-drawn cel animation that gives the impression that the animator (possibly Miyazaki himself) has just stepped out for a moment. With its clutter of sketches, model airplanes, books and art supplies, this room is an animation lover’s fantasy come to life. Miyazaki still works this way, drawing individual frames largely by hand, a process in which the animators take years to draw and ink as many as 140,000 frames for a full-length film.

The second floor is mostly devoted to an art gallery, a mind-boggling exhibition of the art and practice of animation. The walls of the gallery are plastered with hundreds of Miyazaki’s sketches and watercolor paintings, and there are books of storyboards that visitors can thumb through.

The day we went to the Ghibli Museum, the entire second floor was taken up by a special exhibition by U.S. animation powerhouse Pixar, including a mockup of a computer animator’s workspace, along with storyboards and hundreds of stills from Toy Story, Monsters, Inc. and other Pixar blockbusters. The Pixar animators all revere Miyazaki, judging by all the greetings and testimonials plastering the walls.

On the third floor is a full-size “Nekko-bus” (Cat Bus), a huge stuffed toy the size of a minivan, which children can climb inside and relive the famous scenes from “Tonari no Totoro” in which the main characters Mei and Satsuki ride the Cat Bus through the sky. Also on the third floor is a children’s reading room and a shop called Mama Aiuto! (Italian for “Mama, help me!” — a reference to the pirates in “Kurenai no Buta”), which was packed as usual with shoppers snapping up Studio Ghibli-related memorabilia.

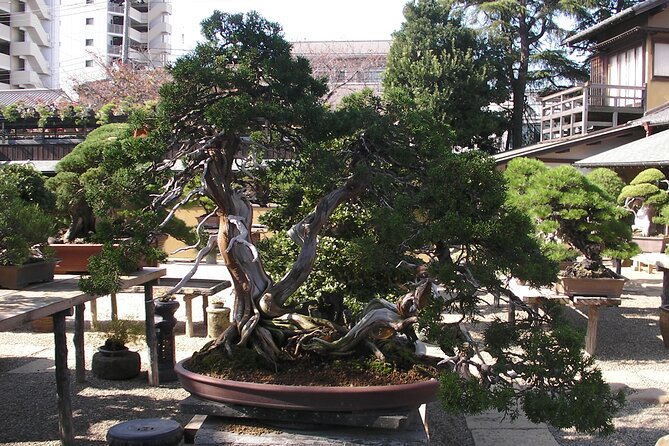

The roof of the museum, accessible by stairs from the third floor, is a riot of life, with overgrown wild grass and trees, crucial and recurring elements in the work of the famously eco-conscious Miyazaki. A full-size, 15-foot-high replica of a robot from “Tenkuu no Laputa” (“Laputa, Castle in the Sky”) graces the grassy rooftop.

Outside on the museum’s patio is a rustic shed with a hand-pump well and the Straw Hat Cafe (another reference to “Tonari no Totoro”), overlooking Inokashira Park, provides a soothing place for footsore visitors to catch their breath and rest their feet beneath a towering pine tree growing through the deck.

Ghibli Art MuseumOpen 10:00-18:00 (visitors must enter at the time on their ticket). Closed most Tuesdays and during New Year’s and periodically for maintenance. Photography is not allowed.Adults: 1,000 yen. Discounts available for children. Tickets available from Lawson’s convenience stores and JTB travel agents.Access from JR Mitaka Station: Walk along the Promenade of Winds to Inokashira Park or take the bus. Visitors are urged to use public transit. There is no parking at the museum.